At first glance, the similarities between doctors and editors may be difficult to imagine. While editing may not have quite the number of specialties as the medical profession, it is no more a one size fits all profession than doctoring is. You may have a general practitioner for annual checkups, but when you break a bone, you’ll be referred to an orthopedic doctor. Sustain a heart attack and you’ll see a cardiologist.

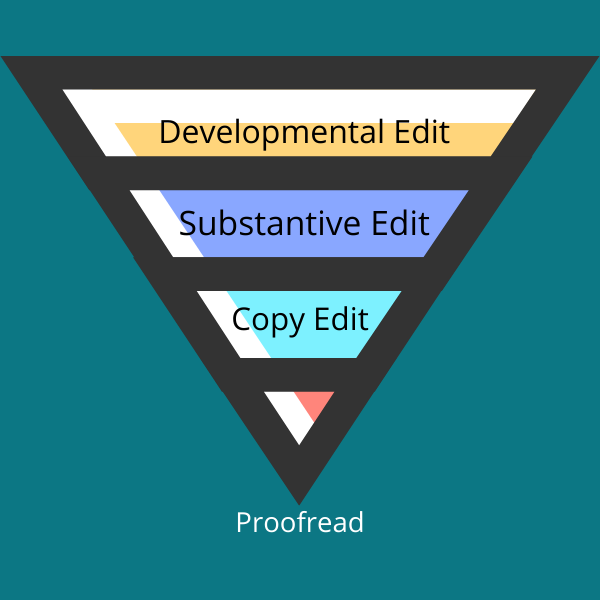

Likewise, it’s important to know that editor is an umbrella term that encompasses as many as five to seven “specialties.” Before we delve into them, however, I want to point out one other similarity between these professions.

Editors don’t actually take an oath to uphold certain standards as a doctor does. However, a good editor—one you’ll want to work with—will adhere to the Hippocratic oath just as your doctor does. They will do their best to do no harm.

Whatever our specialty, our goal as an editor is to make your writing better. An editor worth her rate is knowledgeable in grammar, punctuation, usage, and syntax as well as the latest trends in publishing. Our job is not to impose our preferences on the author nor to apply grammar rules with impunity. Editing is a surprisingly subjective endeavor. Consistency often trumps grammar rules. A good editor retains the author’s voice and deftly applies current standards of grammar and usage. Share on X

Language is dynamic, and culture keeps moving and changing. Unless you’re writing a classic (and you won’t know that until many years later) what attracts readers today is different than twenty or fifty years ago. Writers need to be aware of what publishers are looking for and how to package it. An astute editor will guide an author along the path to publication—be it with a traditional or hybrid publisher or self-publishing. So consider a professional editor an important member of your team. Share on X But first, which editor do you need and when?

Big Picture Editing

First, it’s important to know that there is no universal definition for the various levels of editing. Be sure you and your editor understand what you need and what she is providing. Most agree, however, that developmental, sometimes called substantive or content editing, is the first step.

It might be helpful to think of a developmental editor (DE) as a travel agent. You may come to them with a general destination in mind—a Caribbean cruise, perhaps—but no idea of which cruise line is appropriate for your budget, which islands to visit, or how best to spend your time enroute and on arrival. A travel agent helps you navigate all those decisions.

Similarly, you approach a DE with a general concept of your novel but may not have fully considered your target audience or how to reach them. Or your characters are not fully thought out or developed and you’re not sure how they need to be developed to achieve your overarching message. Or you’re not sure how to organize or structure the content to achieve your goals.

A DE is going to be able to help you organize your book concept in much the same way the travel agent helps you plan the most enjoyable trip possible—things out of your control aside.

Whenever you approach a DE—when your novel is only a concept or an outline or you’ve completed your first draft—be prepared to be challenged and critiqued. Readers come to a novel with certain expectations. Fail to meet those expectations early in your work and you’ll lose your reader. A DE knows what those expectations are and how to meet them within the framework of your plot line. He will identify holes in a plot, failure to develop characters, weak dialogue. She may suggest reordering the timeline or structure to ensure readers are motivated to keep reading and not give up when they are given too much or too little information at the appropriate time.

Depending on where you are in the process, a DE may take on the role of a coach and work with you chapter by chapter. Or they may give an editorial assessment. Depending on the length of the manuscript, this may run several pages and break down all the areas that need attention.

Getting the Project in Focus

With the big picture clearly identified, a copy or line editor is your next stop. Notice that with each step in the process, the focus becomes narrower and more defined. Some sources suggest a paragraph level (stylistic or line) edit next, followed by a sentence-level edit (copyedit).

I approach them as a unit, that is, my copyedits include line editing, which can also be specified as a heavy copyedit. In a copyedit we’ve moved from the big picture to a more detailed look at words, sentences, and paragraphs. We’re looking for readability. Is the prose clear and does it flow? What’s the tone and is it consistent?

Whether we realize it or not, most of us have pet words and phrases. Often, we’re not aware that we’re using them frequently. A copyedit picks up on repetitive words or phrases and recommends synonyms. A related, but more nuanced task is usage. This involves more than assuring that the correct homonym is used. Usage reflects character. An elderly character moves at a different pace and in a different manner than a teenager. Do the verb and language choices reflect that?

Because I cannot overlook punctuation and grammar errors, I include these in my line/copyedit. This includes pointing out inconsistencies. Perhaps an author changed the name of a character or location in the revision process, but a global find and replace didn’t catch every instance. Or a hyphenated term is not rendered consistently throughout. And there may be reasons for that. A good copyeditor knows that most compound adjectives are hyphenated before the noun but not after.

Dialogue is a key component of fiction. A copyeditor must pay attention to proper punctuation as well as use of dialogue tags. Here’s a case of more is less. As long as it’s clear which character is speaking, dialogue tags are not necessary. When they are, limit them to said or asked, and avoid adding an ly adverb to describe how a character speaks. Use their dialogue and the surrounding narrative description to show rather than tell about a character.

Fiction often uses several points of view. If they are not consistent or they change too frequently within a scene, readers will have a hard time following the story. Copyediting catches these inconsistencies.

Final Step – Proofread

The final step in the editing process is proofreading. If you’ve been working with the same editor through your developmental and copy edit, you may be well advised to find another person to proofread. It’s just human nature that by the time you’ve been through a manuscript four or five times, the eye sees what it wants to see, not necessarily what’s on the page. A proofreader is going to focus on typos and consistencies in layout. Their task requires little or no adjustments to the copy itself, unless something is not clear. You may have someone proof your manuscript before it goes to print. .If you’re working with a traditional publisher, you will get a proof copy to review before the final printing.

And Then There’s Nonfiction

Nonfiction editing demands another layer of attention—attention to resources. I could write a separate blog on editing nonfiction and quoting other sources and some day I will. For now, suffice to say that any sources you quote must be identified and properly cited in a footnote or end note—except for Scripture verses which are cited directly in the text.

Failure to credit your sources can leave an author open to charges of plagiarism. Even paraphrased content must be acknowledged.

While song titles are not copyrighted and may be named without citation, lyrics cannot. Copying lyrics without requesting permission may result in significant costs to an author. You can paraphrase or identify them generically, but I, and all the editors I know, discourage our clients from quoting song lyrics.

Do Your Homework

Still not sure what level of editing you need? Many editors do a sample edit. It’s a good way to see how an editor works and get a sense of whether this person is a good match for your project and personality. Others may ask a prospective client a series of questions on an intake form or require a brief phone conference. They’ll want to know about your writing experience, have others critiqued your work—preferably a writers or critique group and not only your closest friends and relatives. They may ask if you’ve worked with a professional editor and what your expectations are for your work. Your answers to these and more questions will give a prospective editor an idea of where you are in the writing process and help him or her know what level of editing will serve you best. Bottom line: be as clear as possible about what you need and understand as much as possible about what your editor provides.

Happy writing!

Leave a Reply